Baseball's peak: Making and breaking the pitcher's mound

Lucas Sims expects a consensus among his Cincinnati Reds teammates about their favorite - and least favorite - MLB mounds. A few hours before a home game in late May, he approaches fellow reliever Emilio Pagán in the clubhouse to test his hypothesis.

Pitching mounds are an unusual feature to begin with. They're the only elevated surface in any major sport, going against the concept of a level playing field.

Relievers in particular are accustomed to seeing mounds at their worst. They might follow a half dozen or more pitchers who created divots and potholes next to the pitching rubber and at the landing area. Relievers are like recreational golfers with afternoon tee times, dealing with dimpled greens on a busy Saturday.

Baseball stadiums all have unique perimeter dimensions but on the infield, every distance is set by rule. The measurement from the back point of home plate to the pitching rubber is 60 feet and 6 inches everywhere, and the mound is expected to be 10 inches above the field at its highest. But what it's made from and the way it transforms over the course of a game are different from ballpark to ballpark.

"Least favorite mound?" Sims asks.

Taken a bit by surprise, Pagán considers the question before answering.

"Colorado," the veteran says. "I don't like the top surface they use in Colorado."

"It's like putty," Sims agrees.

Sims admits his distaste for Colorado could also stem from his memories of playing there. Pitching in the thin air nearly a mile above sea level is generally not a great experience. He owns a career 7.20 ERA at Coors Field.

Pagán adds another contender: "San Francisco is very hard."

Sims nods - he doesn't like Oracle Park either. It's tough to feel confident his landing foot will secure itself to the mound.

"San Francisco is as hard as a rock," Sims says. "Very hard."

Do they speak about mound quality often? "We talk about it every day," Sims says.

"Every day we come in, 'Hey, does the mound looks good today?'" Pagán adds.

They both love Yankee Stadium.

"Everyone says Yankee Stadium is one of the best," Sims says. "Material-wise, feel, the way it holds up. Your cleats sink into it but don't dig into it. There are no holes. It's kind of weird that it's not a universal thing. It's different from place to place. Some places are rock-hard. Some places are kinda soft and get chewed up."

Says Pagán: "They have it down to an art where your cleats go into the mound, but you are not ripping out a hole. You feel you are very well grounded on the mound ... like you can feel the mound through your cleats."

A pitcher's trust in his plant foot is crucial. The kinetic chain begins there: that transfer of energy from a pitcher's interaction with the ground, ultimately reaching their throwing hand.

"In Atlanta, they used to just dump water on it," Sims said of his time with the Braves. "I was starting for most of my time with Atlanta. I'd go throw, like, twice and my whole spike would be caked, the whole underside."

A few weeks later, I asked Kansas City Royals reliever Will Smith about the mounds he prefers. The veteran has pitched in 32 past and present MLB stadiums during his career. While he didn't pick a clear No. 1, he also included Yankee Stadium in his top tier.

"Both New York mounds, D.C., they have that sticky clay," he said. "It doesn't get torn up as much and your cleat sticks in the ground a lot better than most."

Seattle Mariners pitcher Bryce Miller is happy to blow up the idea that Yankee Stadium is the pinnacle.

Miller was walking down into the visiting dugout from pregame throwing in Cleveland when I posed my question. Perhaps he's a homer, but he cites Seattle as a favorite.

His least favorite? "Where was the sandy one?" Miller asks a teammate walking by.

New York, he's told.

"Yankee Stadium is not my favorite," he says. "It is one of the softer ones I was talking about. It felt like my cleats stick a little more. I didn't like that. I like it when it's pretty firm. Whenever it's too soft, you end up digging a hole and that's not good."

In discussions with a variety of pitchers, it's clear there are different preferences for surface types and mound conditions. Quality varies between ballparks and even changes within games.

"Some mounds are significantly worse than others, which is kind of surprising," Sims said. "Some of them are beautiful. Some are just kind of standard. Others hold up well during well during day games, and others, by the third inning it is a rock."

Construction

Since Progressive Field opened in 1994, Brandon Koehnke has been its head groundskeeper.

He grew up in Appleton, Wisconsin, the longtime home of a Chicago White Sox Class A affiliate. There, at Goodland Field, he began working as a member of the grounds crew at age 12.

"Long story short, I basically turned that job into my career," Koehnke says.

What's unusual about Koehnke is he also played professional baseball. A shortstop, he reached Class A with the short-season Boise Hawks in 1987.

After his playing career, he began working on the grounds crews at Florida-based spring training and development complexes. He was hired to be the stadium manager for Cleveland's new spring training home in Homestead, Florida, but Hurricane Andrew flattened the area in the late summer of 1992, before it had even opened. Cleveland then hired him as the caretaker of its major-league stadium.

Koehnke's had the job ever since, and he's constructed an awful lot of pitching mounds in that time.

That construction begins anew each spring, Koehnke explains. The mound sits through winter, and when its tarp covering is removed in the spring, the hill doesn't look like it did when the Guardians' previous season ended.

"It's a hunk of dirt that has to be reshaped," Koehnke says, "You can imagine the freeze, thaw, freeze that will happen. … When we open it up in the spring, it is not a mound. The big component is reshaping it. You re-establish the distance. You re-establish the height."

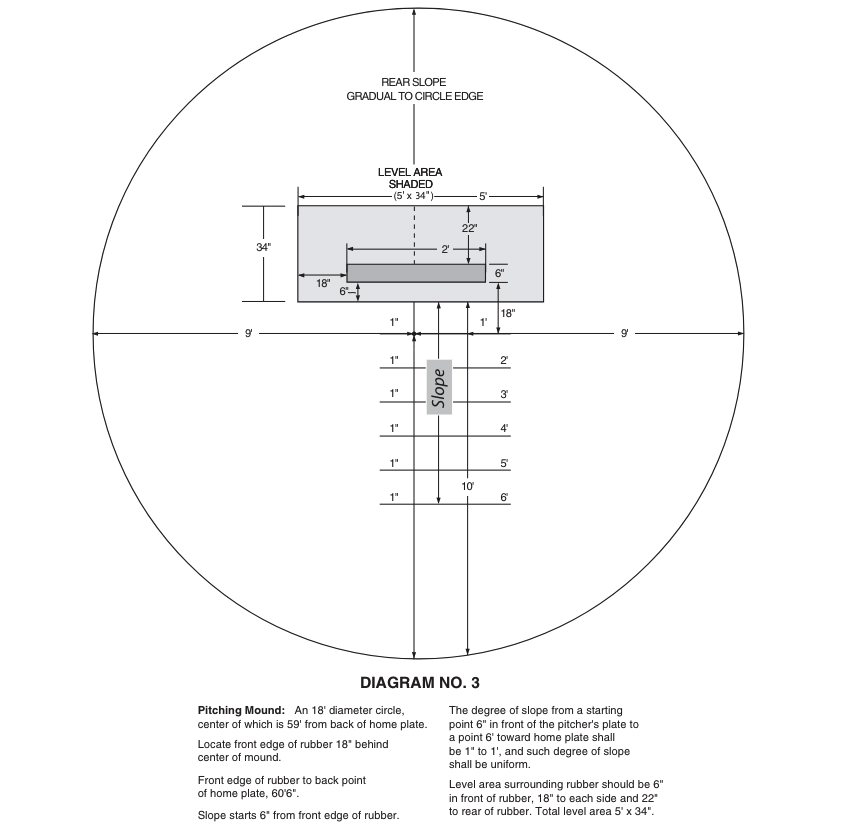

The top of the mound is actually flat, a rectangular area he calls the "platform." According to MLB rules, this flat area must be 5 feet wide and 34 inches from front to back. The pitching rubber, or pitching plate, is centered in the platform's area width-wise but located further forward, toward home plate.

The first 6 inches in front of the rubber are in that flattened space. Then the gradual descent begins. The mound is to descend 1 inch in the first 18 inches toward the plate, and then 1 inch for every foot.

The mound is 18 feet in diameter with the rubber placed nearer the back of the structure, and it's shorter and steeper in the rear compared to its front slope.

How often are the dimensions measured?

"We get measures on a yearly or biannual basis," Koehnke says. "So it's not as if someone is not looking. MLB does a good job of making teams conform to these specifications."

What is the mound made of? Unlike its dimensions, there are no rules on what material is used because climates vary around the continent.

"Take the word 'dirt' out of it," Koehnke says. "The entire mound out there is compressed clay."

Clay is technically not dirt: Clay is comprised of inorganic minerals, whereas dirt or soil contains a whole host of things, including organic material. Crucially, clay can handle the stress of an MLB game.

"Clay will retain some moisture to it through a two-and-a-half-hour game," Koehnke says. "Moisture is what holds it together. … That's what I'm looking for. Something that can withstand the pounding."

Koehnke doesn't believe in soaking a mound before a game, but a mound that doesn't naturally retain moisture is a big problem during a day game.

"Oh boy, is that thing going to dry out," he says. It'll crack and crumble, and the footing will suffer.

On top of the base clay, Koehnke's mound is topped with a light layer of calcined clay: a super-heated variant with coarser grains. This layer doesn't stick to cleats in the event of rain, and it also protects the mound from becoming too dry.

"For lack of a better term, it's cat litter," he says.

In some ballparks, like Yankee Stadium, a layer of calcined clay appears lighter in color on the throwing area and gives the mound a two-tone look.

Do the two clay variants mix throughout the season, creating instability? No, Koehnke says. After games, grounds-crew members remove any debris and calcined clay from the mound. They fill divots and holes in the landing areas with base clay and flatten the repaired areas by repeatedly thumping them with a tamper. The surface is once again pristine - ready to be re-topped, then scratched, clawed, and cratered the following day.

Perception

While mounds are the same height and distance from home plate (or at least they're supposed to be), the way pitchers perceive them is different.

Pitchers say they detect differences in mound height. Back in May, several Dodgers pitchers said the mound seemed lower at Great American Ball Park in Cincinnati.

"I know this one looks a little shorter, but our field is crowned," Pagán says. "I had this conversion with our head grounds-crew guy. He said because of the slope of the field, you cannot build up the mound any higher. It does look very short, but once you start throwing it feels the same."

Koehnke said most modern fields are perfectly flat, which is verified by laser surveying, but other ballparks might be crowned - featuring an elevated center portion sloped downward from the infield - to help with drainage.

On other mounds, pitchers feel taller.

Guardians pitcher Shane Bieber said he feels more elevated in Toronto. He owns a 3-0 record and a 2.01 ERA in three career starts at the Rogers Centre.

Mariners starter George Kirby believes perception matters.

"I like to feel on top of guys. A good downslope," he says. "Backdrop kinda matters, too. There are some places with funky backdrops."

For instance, Kirby feels taller on the mound in Oakland, but visually, he doesn't like the field-level suites added in front of the original wall in Oakland's spacious foul territory. "Sometimes it feels like you are further away than 60 feet," he says.

Kirby owns a 3.36 career ERA but a 4.26 mark at Oakland Coliseum.

"Perception-wise, it's hard to explain, but some places when you look at the catcher, it almost looks shorter," Mariners teammate Logan Gilbert says. "Some places are the opposite. Not sure why it works out that way."

They each feel closer to the plate at T-Mobile Park. Does that psychological element matter? Gilbert owns a career 3.72 home ERA compared to a 3.43 mark on the road. Kirby owns a 2.83 ERA at home and 3.89 mark on the road. It's tough to know.

Etiquette

If a pitcher doesn't like the state of the mound, he can call for help.

The grounds crew will come out and fill a divot that might affect his landing spot, or a drying agent can be added to absorb water if it has been raining.

Social pressure, however, can affect the decision to ask for help.

"Last year, I was pitching at home against Lance Lynn. He dug a giant hole, like a crater," Miller says. "In the fourth inning, it got to the point where I was dragging my foot, and I got a blister right here. I took my shoe off and I was bleeding and I had to deal with it for the next month. That's not fun. Last year, I was too scared to say anything because I was a rookie. It was like my 10th start. I don't want to be complaining about the mound. But if it happened again this year, I would have them fix it."

Pagán says he tries not to pause the game if possible.

"The last thing we want to do is call the grounds crew out to fix something you can probably pitch around," he said. "At the same time, it's a very important part of the game. There are some guys, because of the force they put in the ground, they create bigger holes. Where you run into trouble is if it's where your toe or heel normally sits, because then you are off balance."

Pitchers generally have slightly different stride lengths and landing points, so it's not an issue. But sometimes they overlap in awkward ways.

"There's a balance there," Pagán said. "I need it to be good enough to pitch, but I can pitch through some stuff. One time I just moved over on the rubber because there was this huge hole. No big deal, I thought. And with my first pitch, I smoked the guy in the helmet. I thought 'OK, I have to move back to the other side.' Just a little bit of a shift and your release point is different, everything moves differently.

"I ended up sending a text to the guy on the other team, 'My bad, I wasn't trying to hit you.'"

Koehnke even likes the interactions when he's called out to make fixes. "It's always kind of cool to end up talking to somebody out there."

What the pitchers and grounds crew know is that every time there is a visit, the playing surface they encounter won't be quite the same.

"All the mounds are different," Kirby says. "I feel like you're never going to get the same one."

Travis Sawchik is theScore's senior baseball writer.

HEADLINES

- Watch: Yankees' Volpe accidentally hits Judge in face with baseball

- Yankees' Schmidt expected to require Tommy John surgery

- Bobby Jenks, former All-Star White Sox closer, dies at 44

- Welcome to 3,000: Scherzer reflects after Kershaw joins K club

- Red Sox rout Nats to secure 10,000th win in franchise history